Cléoma Breaux was born on May 27, 1906. I know this because, several years ago, I collaborated with a Dust-to-Digital intern to build a comprehensive calendar of artists whose birthdays or death anniversaries I wanted to highlight on social media. Even when I do not end up posting about artists—which was the case for Cléoma a month ago—I usually take time to reflect on their lives and music. On that Tuesday in May, I thought back to when I first heard her with her brothers and Joseph Falcon on the 1929 recording of “Acadian One-Step” via the Anthology of American Folk Music and used that memory as the springboard for this writing.

Cléoma began her life in Crowley, Louisiana, a town that offered both rural and urban ways of living. Raised in a musical home, she and her brothers, Amédé and Ophey, followed in the footsteps of their father, Auguste Breaux, a skilled accordionist. Largely self-taught, the siblings would become multi-instrumentalists and form the Breaux family band. When their father abandoned the family in 1917, music became both a unifying force among the siblings and a vital source of income for their family.

In 1921, at the age of 15, Cléoma married a Crowley-based guitarist named Oliver Hanks. The union was short-lived and the couple divorced soon after. As time went on, Cléoma and her brothers’ notoriety for entertaining at Crowley dancehalls spread throughout the area. Joseph “Joe” Falcon, an accordionist who was born in 1900 in nearby Rayne, came to see the group at some point in the mid-1920s and fell for Cléoma. The two began performing as a duo, and with the support of a music enthusiast named George Burr, they would soon make recorded-sound history.

George Burr, who Cajun music historians Ryan Brasseaux and Kevin Fontenot described as Joe Falcon’s manager in the 2009 book Louisiana Women: Their Lives and Times, ran a jewelry store in Rayne. In a 1962 interview with Chris Strachwitz, Joe recalled how, in 1928, George had driven him and Cléoma 150 miles to New Orleans in hopes of making a record.

Having heard about a Columbia Records recording session, George felt strongly that Cajun music should be available on phonograph records. According to Joe, when they arrived in New Orleans, a Columbia representative initially dismissed the idea of recording an accordion-and-guitar duo. But George was undeterred, pulling out a blank check and offering to prepay for 500 copies of the record. As Joe later recounted, here’s how the conversation went:

George Burr: “They’re popular where I’m from in Rayne. Them people’s crazy about this music and they want the record.”

Columbia Records representative: “We don’t know if it’s going to sell.” Then they asked him, “How much would you buy?”

George: “I want 500 the first shot.”

Columbia representative: “Aw, 500. When you going to get through selling that?”

George: “That’s my worries. It’s not yours. Run it through. I want 500.” He pulled out a blank check and he said, “Furthermore, make you a check for 500 records. I’m going to show y’all I want them.”

They started looking at each other. They said to Joe, “You go ahead and play a tune just for us to hear.”

Joe recalled opening his accordion inside the building, which he remembered being large but the space they were in being closed off, which amplified the sound. “That thing was sounding like it wanted to take the roof off. When I played that number they started talking to each other.” Joe said the Columbia Records staff remarked how it was more music out of two instruments than they have ever heard. They then told Joe and Cléoma, “Let’s try one.”

The songs they played were “Allons à Lafayette” and “The Waltz That Carried Me To My Grave,” and on that Friday, April 27, 1928 in New Orleans, the first commercial record of Cajun music was made.

The record was a success, selling 19,249 copies. According to Joe, “Even some of the poor country fellows they buy two records, they didn’t have a Victrola. Sure enough. Buy it and go through the neighborhood and play it.” Columbia Records invited Joe and Cléoma to New York City that August, where they recorded six more sides. The following April, they recorded again, this time in Atlanta. For that session, which produced twelve recordings, Cléoma and Joe were accompanied by her brothers Amédé and Ophey.

When the Great Depression hit in 1929, the recording industry slowed dramatically, and from 1930 to 1934, no Cajun records were produced. During this time, Cléoma, her brothers, and Joe found steady work performing in Louisiana dancehalls, promoting themselves as Columbia recording artists. In 1932, Cléoma and Joe married, and not long after, they adopted their only child, a daughter named Loula.

In 1934, as the economy was beginning to recover, Joe and Cléoma began to record once again, but with different labels. Columbia was out, replaced by the more budget-friendly Bluebird and Decca. Over the next several years, the duo would alternate between the two companies with twelve recordings coming out on Bluebird and 40 recordings on Decca.

After the Depression, not only had the record labels changed, but so had Joe and Cléoma’s music. Most notably, Cléoma was branching out from Cajun music to sing blues, country, jazz, and pop songs almost always in French but some in English. A striking example came on Sunday, February 21, 1937, when the duo recorded ten tracks for Decca at the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas, Texas. Among them was “Lulu’s Back in Town,” a song originally featured in the 1935 film Broadway Gondolier and later made famous by Fats Waller.

Accompanied by Moise Morgan on fiddle, Cléoma demonstrates an affinity for a jazzier style of music by restraining her usual vocal range to fit the song. As Wade Falcon points out, this recording is “one of the clear evidences of popular music influencing Cajun musicians in the 1930s.”

Sadly, it was during one of the recording trips to Texas in 1937 that Cléoma was seriously injured when her sweater became caught in a moving vehicle, dragging her for a quarter mile. The accident ended her recording career, and just a few years later, in 1941, Cléoma passed away at the age of 35.

Only 31 years of age when the tragic accident occurred, we are left to wonder where Cléoma’s music would have gone had she lived for decades more.

This month saw the addition of two death dates to the artist calendar I manage for Dust-to-Digital’s social media. Both Brian Wilson (born in 1942) and Sly Stone (born in 1943) entered the world as Cléoma left (1941). What they would experience in their lifetimes that she never had were the format evolution from 78s to 45s to LPs and other long-play formats, as well as newly-developed, multitrack-recording capabilities. These are important because the technological advancements would allow greater creative space for artists to present their works.

When I was seven years old, I had a personal, portable cassette player that was modeled to look and to perform like a Sony Walkman. I remember my mom letting me purchase tapes from time to time at a local general store, and the two that I cherished the most were each Greatest Hits compilations — one with recordings by Hank Williams, and the other featuring the Beach Boys.

The Beach Boys tape included music from the early part of their career, and I must have listened to it front to back hundreds of times. Like the Hank Williams cassette, the music it featured was from the singles era — Hank’s were primarily issued originally on 78s and The Beach Boys on 45s.

As I grew older, the catchy pop on that Beach Boys compilation appealed to me less and less. It wasn’t until I was 21 years old, working as a DJ at a college radio station in Atlanta, that the Beach Boys would pop up on my radar again. As I’ve written about before, the Smithsonian Folkways reissue of their 1952 release the Anthology of American Folk Music was an act that I believe helped inspire a reissue label revival — Dust-to-Digital, Light in the Attic, Numero Group, Sublime Frequencies all launched in the years soon after. But in that same year of 1997, another release from the past was reissued, not as a straight-up repackage, but as an expanded edition: The Pet Sounds Sessions.

Pet Sounds was originally released in 1966 as a 36-minute long-play album. It marked a transition from the band’s pop singles to more introspective songs utilizing the newly-popularized LP format. Compared to their previous run of hit songs, the album was seen by many as a commercial failure, but it cemented producer and primary-songwriter Brian as a creative force.

For the 1997 expanded, box-set edition, the run time of the audio came in at 256 minutes. Included were the Pet Sounds album in both the original mono mix and a newly-created stereo mix which was overseen by Brian Wilson. Other bonus features were instrumental tracks, vocals-only tracks, alternate mixes, and edited highlights from the 1965–66 recording sessions.

Much like the reissue of the Anthology of American Folk Music, the audience’s reaction was strong, but instead of spawning reissue labels, the result was musical artists drawing inspiration from the bonus material to create their own versions of Brian-Wilson-sounding aural creations. Using modern technology such as looping pedals, samplers, and digital reverb, solo artists could build walls of sound like Brian had done with the Wrecking Crew studio musicians and his singing brothers, cousin, and friend at Capitol Studios.

In 2011, the follow-up box set The Smile Sessions was released to similar critical acclaim. Its focus was on the abandoned recordings from the Beach Boys’ unfinished 1966–1967 album SMiLE. In 2013, the Dust-to-Digital box set Opika Pende: Africa at 78 RPM lost the Grammy Award for Best Historical Album to The Smile Sessions. But given how big of fans we all were of Brian Wilson, it was hard to begrudge him for winning.

Less than two years after the death of Cléoma Breaux, 400 miles northwest of Crowley, Louisiana, Sylvester “Sly Stone” Stewart was born in the small town of Denton, Texas — just north of Dallas. Shortly after his March 15, 1943 birthday, the Stewart family moved to Vallejo, California — just north of San Francisco.

Sly’s parents K.C. and Alpha Stewart were a deeply religious couple who were very active in the Church of God in Christ. Here is how Sly described the household in which he was raised in Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin), the autobiography he co-wrote with Ben Greenman:

“There were seven of us, and the eighth member of the family was music. Even before children, my parents played. My father played washboard, guitar, violin, fiddle, harmonica. My mother played keyboards and guitar. Music was as much a part of our home as the walls or the floor. The piano was as prominent as the kitchen table. All of us sang from as early as I can remember, and the first songs we learned were gospel songs by Mahalia Jackson, Brother Joe May, the Soul Stirrers, the Swan Silvertones. We built our future in heaven. We dug a little deeper. We put our trust in Him.”

As children, Sly with brother Freddie and sisters Rose and Loretta, formed The Stewart Four. The group, with Sly on lead vocal, recorded “On the Battlefield” and "Walking in Jesus' Name” for a locally-released 78rpm record in August 1956.

At age 13, Sly was playing guitar, bass, and drums at the church six or seven days per week. It was during these events at the church that he first encountered future bandmate Cynthia Robinson. Here is how she remembered that moment in the 2025 documentary Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius) directed by Questlove: “The first time that I saw him was in a youth choir. When Sly would sing, it was just on another level that caused joy in your heart. I never forgot him.”

How I first encountered the music of Sly Stone was by way of hip hop. In some ways, I feel fortunate growing up in a time before the internet. But there were pluses and minuses. On one hand, I did not find out about Sly and the Family Stone until I was a teenager. Thankfully though, as I began to learn about how hip hop music was created — by often taking fragments of pre-recorded music and looping and rearranging those bits into to new arrangements — I found a website called Sample FAQ. Rudimentary in presentation, the site collected and distributed lists of which hip hop songs sampled which tracks from the past — offering a DNA blueprint for hip hop recordings. It has since been replaced by the more-modern Who Sampled website, which includes time-stamped audio in its presentation so listeners can go directly to where each sample originates.

What I didn’t realize until those educational moments online is that I had been listening to Sly’s music for years — it had just been embedded in new works. When I was a DJ at the college radio station, I was able to access to all of his 1960s-70s albums, but by that time Sly’s musical career had become dormant. Songwriter and producer Terry Lewis, who with Jimmy Jam sampled Sly & the Family Stone's “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” in Janet Jackson’s hit song “Rhythm Nation,” made a point in the recent Questlove documentary about Sly’s position in music during the 1980s-90s: “He had influenced so many different artists, but new supersedes old, always. So, the same musicians influenced by Sly Stone became his competition.”

On May 29, 2025, two days after Cléoma Breaux’s birth anniversary, I attended The Big Screen: Historic Psychedelia, Animation, and Avant-Garde Films in Large Format. The event was curated by Andy Ditzler who for years has been putting on screenings around Atlanta as part of his Film Love initiative. On that Thursday evening at the Plaza Theatre, Andy and his colleague, Emory film professor Gregory Zinman, presented ten films, including The Dante Quartet by Stan Brakhage.

The Dante Quartet is a seven-minute experimental short from 1987 consisting of images that Stan Brakhage painted directly onto IMAX film, 70mm film, and 35mm film, mostly over footage from other films. Divided into four sections, the film serves as a literary adaptation of The Divine Comedy.

For the final section of the film, in lieu of the word “heaven,” Brakhage uses the phrase “existence is song” for the title card. This resonated in my mind throughout the night, and I wondered the next day if there was a clue to phrase’s origin in Brakhage’s “The Test of Time” radio shows. I felt like if there was a relation to music in its meaning, those shows that Stan produced in 1982 could hold the answer. I did a search of the transcripts for all 20 episodes, and unfortunately, it proved to be a dead end, so I emailed Andy Ditzler to see if he knew the reference. He told me that the text was Brakhage's re-quoting of a Rilke poem, where the original German is “Gesang ist Dasein,” sometimes translated as "Singing is Existence" and sometimes as “Singing is Being.”

I was grateful for Andy providing me with the lead, and I used it to locate the source: “The Sonnets to Orpheus,” a cycle of 55 sonnets written by Rainer Maria Rilke in 1922.

In the third sonnet, Rilke states “song is existence” which Brakhage reinterprets in his film’s title card as “existence is song.”

In 1964, Swiss historian Jean Rodolphe Salis wrote his interpretation of Rilke’s text:

“In these three words Rilke coined the shortest, most concise definition possible of the art he practised, as he practised it. After his great poems were written Rilke the artist was once more one of the ‘favourites of fond creation,’ as he called the angels in the Elegies. But ‘song is existence’ meant also that his creative work depended on his state of spirit, mind and body being natural, free and light. Having found his way back to himself after such long detours he was borne along by the current; it seemed to him like breathing - or:

‘An aimless breath. A stirring in the god. A breeze.’”

Using this rubric of creative work’s dependence on the spirit, mind, and body being natural, free, and light, I decided to apply it to the three artists highlighted above.

Brian Wilson, like Sly Stone, grew up in a musical family. His father Murry was a machinist and part-time songwriter, and he and wife Audree would often play duets on the piano and organ. Their house was also filled with recorded music as the couple enjoyed listening to records by artists like Henry Manicini and Rosemary Clooney. In an interview with Byron Preiss, Murry recalled that when Brian was just 11 months old, he was able to hum the entire song “Caissons Go Rolling Along” while Murry sang it.

Also like Sly, Brian participated in the music program at his church, and by the age of seven, he was regularly singing as a soloist with the choir behind him. The music director at the Inglewood Covenant Church determined that Brian, even after losing almost all of the hearing in his right ear, had perfect pitch. At home, Brian encouraged his younger brothers Carl and Dennis to sing with him, and in his memoir I Am Brian Wilson, which was also co-written with Ben Greenman, he recalls the three of them harmonizing the song “Come Down, Come Down from the Ivory Tower” while they laid in their beds at night.

Brian taught himself to play piano, and in 1958, he was given a tape recorder for his 16th birthday. He used the machine to experiment with recording different vocal combinations and various sing-along techniques. In 1961, he began singing with his cousin Mike Love who remembered sleepovers with Brian where they would have stay up late listening to rhythm and blues on a transistor radio.

Around this time, Brian heard the Four Freshman and began to intensely study the arrangements on their records. Inspired by the Four Freshman harmonies, as well as the Everly Brothers and Chuck Berry, Brian decided to form his own group with brothers Carl and Dennis, cousin Mike Love, and high school friend Al Jardine. They would purchase equipment, and the first song they would produce was “Surfin,’” the fulfillment of a dream Brian had had since he was a young teenager.

More songs would follow, and so would touring, but at the conclusion of the Beach Boys tour in 1964, Brian decided he was finished with going on the road with the group. In his time off, he claims he began to understand how you could create emotions through sound. He cites the song “Be My Baby” and the singing of Dionne Warwick and Aretha Franklin as teaching him how singers could “make you feel amazing things with small vocal gestures.” These thoughts helped inspire Pet Sounds. Here is Brian’s remembrance of making of the album in I Am Brian Wilson:

“I love the whole Pet Sounds record. I got a full vision out of it in the studio. After that, I said to myself that I had completed the greatest album I will ever produce. I knew it. I thought it was one of the greatest albums ever done. It was a spiritual record. When I was making it, I looked around at the musicians and the singers and I could see their halos. That feeling stayed on the finished album. I wanted to grow musically, to expand our horizons and do something that people would love, and I did it.”

Building on his creative success, here is Brian writing about SMiLE, a project he began right after Pet Sounds and which would remain unfinished for 50 years:

“That’s the album we started, a way of collecting poetry and sounds and myths and making a perfect thing from them. I was trying to create a spiritual vibe and love for the listener. It was partly about forgetting the ego, which is the reason all the letters are capitalized except for the lowercase i. I was trying to put my arms around everything that music could do, which was everything.”

After performing in doo-wop groups in high school, Sly enrolled at Vallejo Junior College where he encountered music professor David Froehlich. At that time, Froehlich was in his mid-30s, and after growing up in Oakland, he had received a composition degree from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. Here is Sly writing about his teacher in his memoir Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin):

“I always loved singing and playing, loved hearing songs. Mr. Froehlich was the first person who made me love music as a language. He could read music. He could write it. He could hear it and he could speak it. And he wasn’t the kind of guy who stood up on a tower and looked down on the rest of us. He was cool, down-home, regular. I liked that about him.

What did I learn from him? Everything. We did ear training, which taught us to recognize chords, scales, intervals, and rhythms. Then we went deeper, reading Walter Piston, a composer who taught at Harvard University and wrote music-theory books like Harmony, Counterpoint, and Orchestration. Big books—Orchestration was almost six hundred pages—filled with big ideas. Cadences, irregular resolutions, raised supertonics.

Above all, I learned how to learn.”

Sly’s relationship with Professor Froehlich is revisited in the documentary Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius) when Sly remembers him telling him to leave college after just six months: “You don’t need it anymore. You just go do what you gotta do.”

The post-college evolution for Sly began in 1964 at the radio station KSOL in San Francisco. This is where he changed his name from Sylvester “Sly” Stewart to Sly Stone for his DJ name. Inspired by comedian Lord Buckley, Sly Stone’s on-air persona and knowledge of records led to invitations to play on band’s records, which led to producing artists like Grace Slick and Billy Preston, which led to saxophonist Jerry Martini approaching Sly to start a band with him.

Not long after forming a group with Jerry, Sly asked his brother Freddie about possibly merging their bands. In 1967, Sly Stone combined his group, Sly and the Stoners, with his brother Freddie’s band, Freddie and the Stone Souls. The newly formed ensemble, Sly and the Family Stone, featured Sly on organ, Freddie on guitar, and their sister Rose on keyboard. The group also included white members—drummer Gregg Errico and saxophonist Jerry Martini—alongside trumpeter Cynthia Robinson and bassist Larry Graham.

This diverse lineup, bringing together Black and white musicians as well as men and women, made a statement. Sly addressed his view toward racial diversity in his autobiography: “Some KSOL listeners didn’t think a R&B station should be playing white acts. But that didn’t make sense to me. Music didn’t have a color. All I could see was notes, styles, and ideas.”

By 1969, the group was thriving and experiencing success. Sly wrote about his creative process at the time he was producing Sly and the Family Stone’s fourth album A Whole New Thing. He claimed his aspiration was to show his ambition and desire to do something timeless:

‘Stand!’ was backed with ‘I Want to Take You Higher,’ which was proof of evolution. That was the song that had been with me for years, in some form, starting out as a Billy Preston song called ‘Advice,’ resurfacing as ‘Higher’ on A Whole New Thing. Here it was again, new clothes on a stronger body. Freddie opened up with a tight, strong guitar line, and there was shouting, stabbing horns, and the ‘boom-shaka-laka’ chant. What did people think of that? Was it supercharged doo-wop? Something African? Nonsense? No matter how it seemed, it pushed at what they knew or thought they did.

‘I Want to Take You Higher’ was a song I especially liked to play live. It was always one of the last songs in the set, which meant that we could bring the crowd up to where they needed to be and leave the place still vibrating.”

Since their passings several weeks ago, much has been written about the successes that Brian and Sly each experienced followed by their subsequent downfalls. In the aforementioned Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius) documentary film released earlier this year, historian Mark Anthony Neal addresses Sly’s post-Woodstock reclusiveness and addictions: “There’s never been a Black Elvis, right? So, you can’t go to this mythical Black Elvis and ask, ‘What do I do next?’” What seems apparent is that neither Sly nor Brian knew what to do after they were both celebrated as geniuses and their audiences’ expectations were set so high.

While critics and fans mourn the recent deaths and continue to consider the lives and careers of these two musical visionaries, I return to Cléoma Breaux who came of age in a time of less recording technology, less economic opportunity, and less access to the music beyond her community.

Like Brian and Sly, Cléoma’s musical foundation began at home with a creative connection to siblings. Unlike Brian and Sly, there is no memoir that records Cléoma’s life and thoughts. In fact, we don’t even have an interview with her. All that exists are folklorists Ralph Rinzler’s and Chris Strachwitz’s interviews with her husband and musical partner Joe Falcon and an interview with her daughter Loula that was conducted by writers and historians Ryan Brasseaux and Pat Johnson.

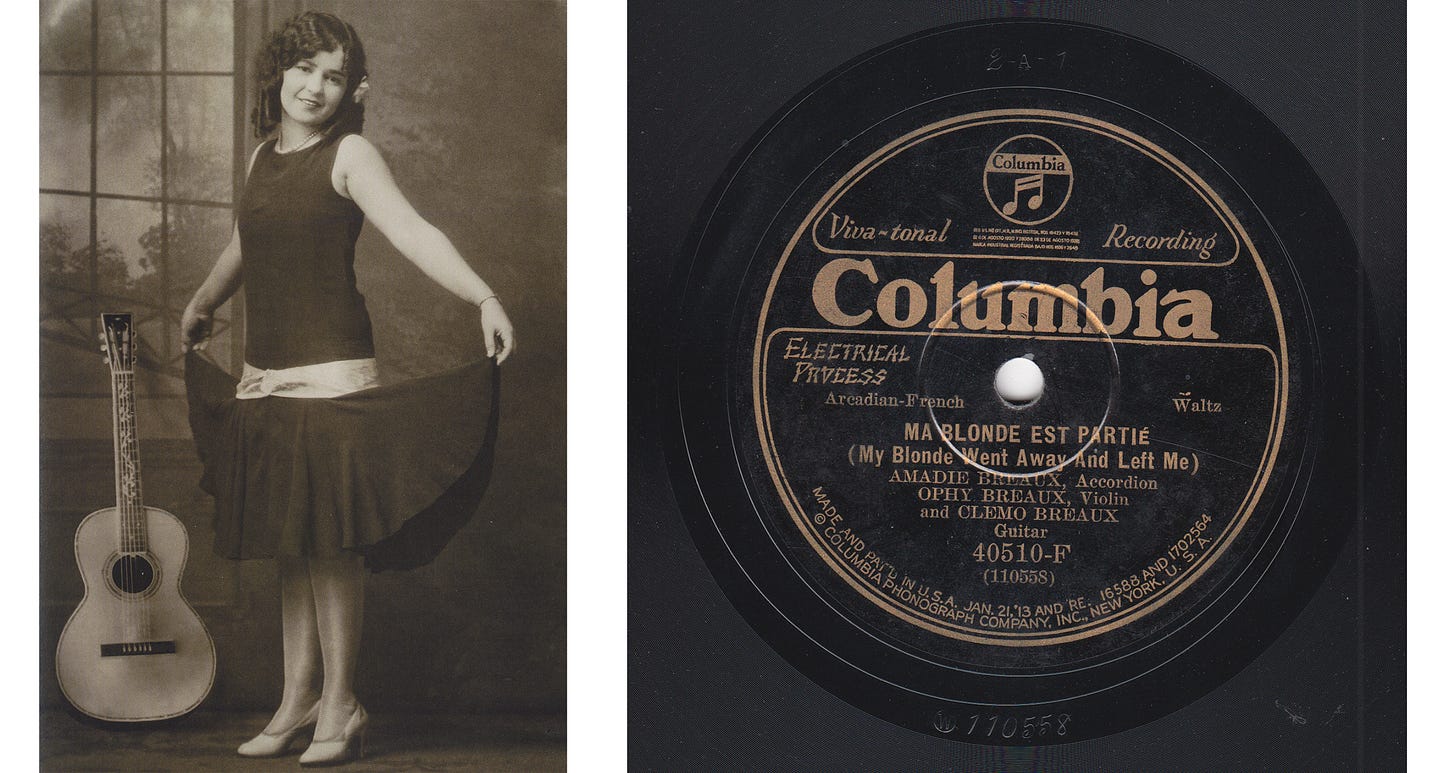

But even with those few glimpses into her life, we can observe greatness and the evolution of an artist. For example, in 1929, when Cléoma’s brothers accompanied her and Joe on their recording trip to Atlanta, the musicians initially set up to perform as a four-piece. They cut eight sides when Joe decided to sit out and let the siblings record as a trio.

The first song the Breaux family group played was “Ma Blonde Est Partie (My Blonde Went Away and Left Me).” Using an old Cajun melody, new lyrics were sung by 28-year-old Amédé, who was credited by the record company as the composer. It was not until Cléoma’s daughter Loula was interviewed years later that she set the record straight. It was her mother Cléoma who actually wrote the lyrics — a fact that has been accepted by the entire family.

Why is this detail important? Well, the song went on to great heights after it was recorded, and even greater heights after Cléoma’s death. The composition showed up on several different record labels under different names in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Then in 1936, the Hackberry Ramblers recorded the song using a title that would stick for good: “Jolie Blonde.” Ten years later, Harry Choates would record “Jolie Blonde” in a more Western-swing style, and the rest is history. The song reached #4 on the Billboard country charts twice in 1947, a feat that would lead to it becoming known as the Cajun national anthem. It has since been performed on national tours by such artists as Joan Baez and Bruce Springsteen, and in 1958 it was the first song that Waylon Jennings and Buddy Holley ever recorded together with King Curtis on saxophone.

Given these stories of Cléoma’s impact on Cajun music — how she was an active participant in its first commercial recording and a writer and performer on what became its national anthem — had she lived a long life, she very likely would have continued to shape the culture. But for Cléoma, like Brian and Sly, their music will be what continues to live on via the recordings they made and the artists they inspire.

I think back to Rilke’s quote, “song is existence,” and its suggestion that to sing, to express, and to create is to live; and Brakhage’s inversion of the quote into “existence is song” as if to say life itself, in all its moments and movements, is inherently poetic and expressive. Together, their words form a dialogue across time, a lyrical meditation on the deep entwinement of being and art — an entwinement I am thankful to experience in works by artists like Cléoma Breaux, Sly Stone, and Brian Wilson.

A tour de force of memory and connection.

🌻 Thank you for this wonderfully enjoyable article. Esp. Cléoma Breaux and the back story of Jolie Blonde, since I am read James Lee Burke at the moment 😺🌻❤️🌻