The Music Always Around Us

Songs and dances as prayers, heightened curiosity as success, and other recent inspiration from new works.

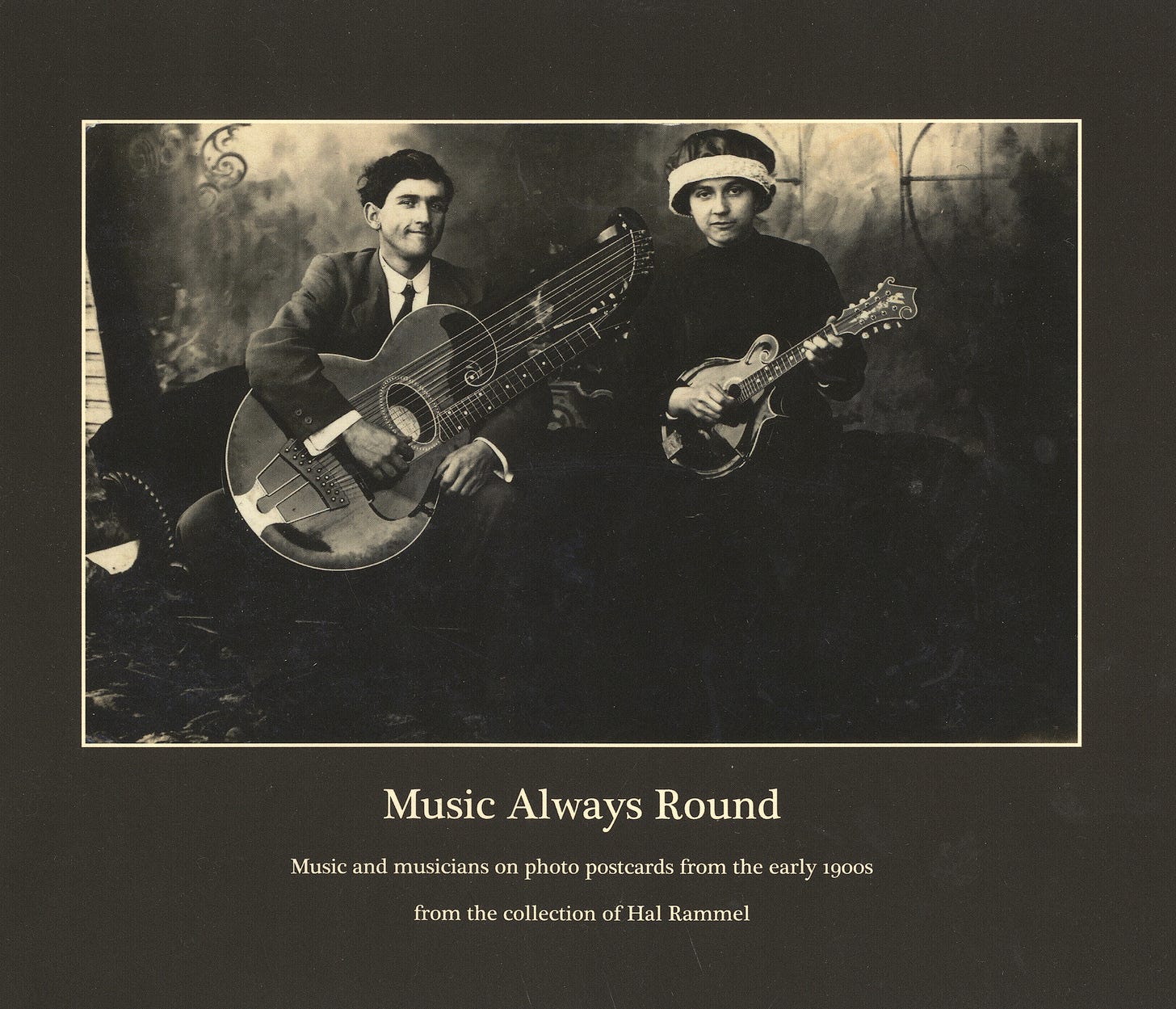

In his new book of vintage, music-related postcards, Hal Rammel cites Walt Whitman’s “The Music Always Around Me” as a key inspiration. The poem, which surveys the musical landscape that Whitman witnessed during his mid-1800’s travels, begins by describing the “music always round” him as “unceasing” and “unbeginning.” It concludes with the following verse:

I hear not the volumes of sound merely, I am moved by the exquisite meanings,

I listen to the different voices winding in and out, striving, contending with fiery vehemence to excel each other in emotion;

I do not think the performers know themselves—but now I think I begin to know them.

In her new book, California Gold: Sidney Robertson and the WPA California Folk Music Project, author Catherine Hiebert Kerst includes an excerpt from a 1930s newspaper article written by folk music collector Sidney Robertson. Entitled “The Spirit of a Generation Reflected in Folk Songs,” the article that Robertson penned echoes Whitman’s sentiment of being surrounded by music:

“How does one find songs? They are everywhere at hand. A man changing a tire on Shattuck avenue in Berkeley last month sang an old ballad as he worked, and was startled by an urgent request to repeat it so it could be written down. A receipt for a bill paid to a railway express delivery man was signed with a Basque name; this led to a whole nest of songs.... And one man in Shasta county offered to ‘outsing the gas tank’ if he might ride along to Fresno.”

Each year, the National Council on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts create short-form documentary films to recognize that year’s National Heritage Fellows. Among the 2024 vignettes, the one that resonated the most with me focused on fiddler Trimble Gilbert, the traditional chief and reverend of the Neets’ąįį Gwich’in people from Vashrąįį K’oo, Alaska.

In the film, Sarah James, an elder of the Vashrąįį K’ǫǫ people, spoke about their community and Trimble’s musical role in it:

“We are Caribou people. All 15 villages. And when they were forced to be colonized into village life, they chose this place because the Caribou migrate through this valley...

Trimble gave a lot of good times dancing. And he gave us a lot of prayers. All of our songs and all our dances are prayers.”

In Ian Brennan’s recently-published book Missing Music: Voices from Where the Dirt Roads End, Scottish percussionist Dame Evelyn Glennie writes about her approach to music in the foreword:

“‘Success’ is not a word I relate to, because becoming better at something is a never-ending patient journey. I am constantly weeding my sound garden and trying to become a better percussionist and musician. If I had to define ‘success’ it would be the heightened curiosity I have been able to sustain, the wonderment in seeing a street performer or a baby handling a rattle for the first time or witnessing the great orchestras of the world or the local pub folk group. I love it all.”

Circling back to Whitman, in his poem “Starting from Paumanok,” which also appears in his book “Leaves of Grass” alongside “The Music Always Around Me,” he includes this text:

Strains musical flowing through ages, now reaching hither,

I take to your reckless and composite chords, add to them, and cheerfully pass them forward.

Each of these recent publications serves as a reminder that we are all the continuation of our musical ancestors — doing our part to contribute to the infinite song.