We are thrilled to announce a new release in collaboration with David Evans, marking the latest chapter in our long-standing partnership. Our work together began 22 years ago when David wrote the liner notes for disc six of our inaugural production, Goodbye, Babylon. Since then, David has been an invaluable contributor to numerous projects, including the release of two albums featuring his field recordings: Sorrow Come Pass Me Around: A Survey of Rural Black Religious Music and From the Lion Mountain: Traditional Music of Yeha, Ethiopia.

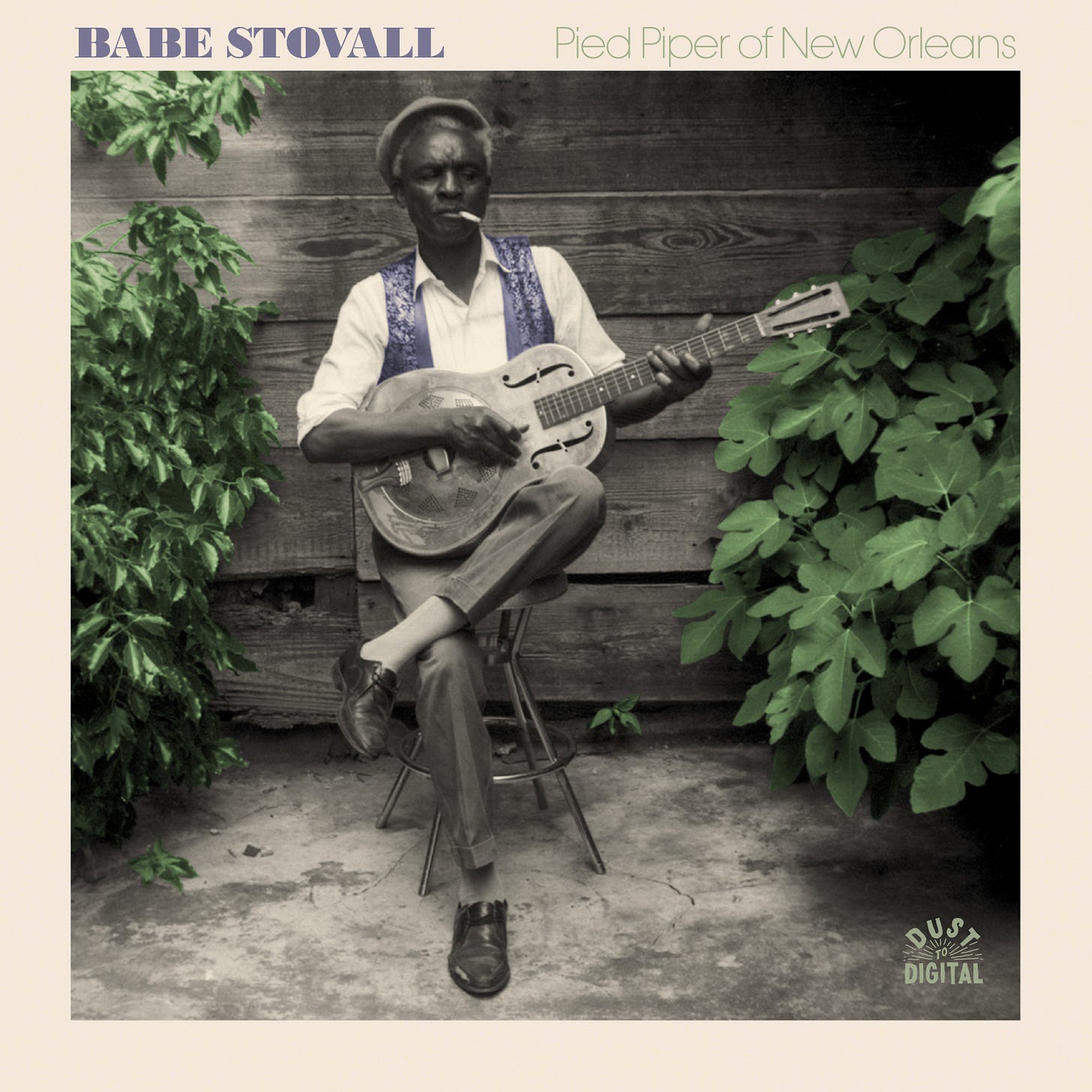

Today, we are excited to share the first in a series of never-before-heard musical releases from David’s personal archive. This collection focuses on the life and music of the remarkable Babe Stovall. Accompanying the digital album is a detailed 40-page PDF, which includes insightful writing by Marc Ryan, Stovall's musical collaborator and the project’s co-producer.

We invite you to explore this musical journey, as David Evans offers a personal reflection on Stovall's life and legacy, bringing new light to a hidden gem of American music.

The 1960s saw a dramatic rise of popular interest in the music of Black American blues singer-guitarists, both in America itself and in Great Britain and Europe. This interest occurred as an extension of the folk and jazz revivals that had started a couple of decades earlier, as well as a reaction to the adolescent focus in the popular music of the era. Blues artists who had been born around the beginning of the century were located by folklorists and amateur researchers and fans, and were recorded, interviewed, and given opportunities to appear at concerts and festivals in America and abroad.

One of the fine blues artists who benefitted from this interest was Jewell “Babe” Stovall, born October 14, 1907, near Tylertown, Mississippi, in the south-central part of the state. The youngest of eleven children of sharecropping parents, he grew up on the large plantation of Seth Ginn, the “boss” of local politics in Walthall County. As a youngster Babe turned to music as a supplement and alternative to the drudgery of farm labor, learning guitar from his older brothers and other local musicians like Herb Quinn, who accompanies him on one track featured on the album. He began by beating rhythms on a lard can, soon advancing to a home-made cigar box guitar and finally a real guitar.

The predominant form of Black music in the area during Babe’s youth was string band music, typically played on some combination of one or two guitars, violin, mandolin, and double bass. It was popular with both Black and white audiences. Blues gradually infiltrated the area’s music during the 1920s, and Babe’s mature repertoire became a mixture of blues, ragtime songs, popular tunes appealing to both races, and a healthy dose of Pentecostal religious numbers. All of these types are heard on this album.

Walthall County was far from any city or the routes typically traveled by the blues stars of the 1920s and later. It was also far from any recording location and thus presented few opportunities for any musician to advance in a career. It was, as well, a site of virulent racism. These factors, along with the lure of industrial jobs, caused many of the Black residents, including musicians, to move across the state line to Louisiana in the 1930s, 1940s and later, either to continue farming or to seek wage work in Bogalusa, New Orleans, or other towns. Babe eventually made the move himself, settling in Franklinton in the early 1950s.

In 1958, he came with his guitar to New Orleans to visit friends and found himself without enough money for his bus ticket home. He began to play for tips on a street corner in the French Quarter and was “discovered” fortuitously by Larry Borenstein, the owner of an art gallery and the building that housed Preservation Hall, a venue for lovers of early New Orleans jazz. Borenstein recognized the value of Babe’s music and began to arrange shows and make recordings of him and to provide other work opportunities. Sometime in the early 1960s Babe and his family settled in the French Quarter, and he managed to make a precarious living playing for tips on the streets, in Jackson Square, and in Preservation Hall and the Dream Castle bar, for a mixture of tourists, jazz fans, hippies, and local residents. He also attracted and welcomed a number of young white accompanists, including future pop star Jerry Jeff Walker and Marc Ryan, who is heard with Babe on several tracks of this album. Marc was among the more serious of these accompanists and tried to help Babe supplement his income by arranging some tours outside the city.

In 1965 and 1966, Babe and Marc made two tours to the Northeast and one to California, but by then the field was somewhat crowded with established Black singer-guitarists, some of whom had made records in the 1920s and 1930s and were considered “legendary.” In contrast, Babe was someone that most blues and folk fans outside New Orleans had never heard of. Besides, Babe didn’t adapt too well to the concert format of playing sets of 45 or 50 minutes and waiting to the end to get paid by the promoter. He preferred to play a song or two and pass the hat for tips, and soon he reverted to this more comfortable pattern back in New Orleans. He managed to keep it up, more or less successfully, until his death in 1974.

I and collaborators Marc Ryan and Marina Bokelman recorded the tracks on this album in four separate sessions in Louisiana in 1966. They present a cross section of Babe Stovall’s repertoire. The blues tracks include pieces from the local oral tradition, such as “Married Woman Blues,” “Three Women Blues,” and “Big Road Blues,” the last of which he learned from famed bluesman Tommy Johnson who had married a woman from the Tylertown area and lived with her there for a time in the late 1920s. Other blues heard here were learned from popular “race” record hits of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. They include the medley of “Prisoner Bound” (Leroy Carr, 1928)/”Big Leg Woman” (Johnnie Temple, 1938), and “Kansas City Blues” (Jim Jackson, 1928), “How Long Blues” (Leroy Carr, 1928), “One Dime Blues” (Blind Lemon Jefferson, 1927), and “Coal Black Mare” (Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, 1941). Babe plays them, as he does on all of his songs, with a strong duple beat on the guitar, eschewing the “swing” rhythms that would become increasingly prominent in the 1930s and later. His ragtime and social songs are all products of oral tradition and include “Boll Weevil [heard above in the audio player],” “Candy Man” (his signature song [heard below in the audio player] and on the album in two versions), and “Salty Dog,” the latter with some salacious lyrics. Finally, there are the Sanctified spirituals “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” “Do Lord, Remember Me,” “When the Saints Go Marching In,” and “The Ship Is at the Landing” (another special favorite with audiences).

Babe is accompanied on some of these songs by Marc Ryan, representing his sound as it could often be heard in 1966 on the streets of New Orleans and in the Dream Castle, and by various longtime musical partners from Tylertown, recreating his sound from earlier years. Herb Quinn, who plays violin on “Three Women Blues,” was about nine years older than Babe and the dean of the Tylertown string band musicians. He played guitar, mandolin, violin, and string bass and once had been a powerful singer, though he was more or less retired from music by 1966 and living and farming near Clifton, Louisiana. Babe had known and performed with him off and on since the 1920s.

Roosevelt Holts, born in 1905, is the featured singer on “Doodleville Blues” (celebrating a neighborhood in Jackson, Mississippi), where he is accompanied by Babe on second guitar. He only took up music in the late 1920s and played less often in string bands, modeling himself more on the popular guitar-playing blues artists of the day. Roosevelt was a cousin of the woman that Tommy Johnson married, and he followed Tommy and his wife to Jackson. There he got in trouble around 1932 and spent four years in Mississippi’s Parchman Penitentiary on a murder conviction. He had the talent to become a star in the blues world, but the prison sentence blighted his career, reducing him to performing locally in Mississippi and Louisiana while doing farming, odd jobs, and various “hustles” such as bootlegging. He died in 1994 in Bogalusa, where he had been living since 1966.

Dink Brister, heard on mandolin on “I’m Goin’ to New Orleans,” and O. D. Jones, heard on guitar and a bit of singing on “Coal Black Mare” and “Big Road Blues,” were among Babe’s old string band partners from Tylertown. Both had moved to New Orleans after World War Two and found steady work respectively in a steel mill and on the docks. Dink was born in 1914 and as a young man learned mandolin from Herb Quinn. Two of Dink’s cousins were married to older brothers of Babe Stovall. One of these cousins was also a niece of Herb Quinn. Dink Brister passed away in 1991. O. D. Jones was born in 1913 and learned guitar from his father and from Dink Brister’s cousin who had married O. D.’s older sister. In addition to string band music, he sometimes performed as a solo bluesman and played a few times with Tommy Johnson in the Tylertown area. He passed away in 2004. All of these artists, as well as Babe Stovall himself, will be heard on further Dust-to-Digital albums in this series of field recordings.

— David Evans, 2024

Today, in celebration of Bandcamp Friday, all the links in the message are directed to our Bandcamp page. Also, we’re offering discounts on several offerings on that platform:

Where Will You Be Christmas Day? (30% off)

Our Digital Discography (60% off + a Bonus Download Code to give as a gift)

For our Substack paid subscribers, we’ve added a link to the Babe Stovall album below, so you can enjoy it immediately.

We hope you enjoy this new release and the special offers available today. Thank you for your continued support!